STANFORD, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Rumors and speculation abound when it comes to discussions about CEO succession at high-profile companies such as Ford, Proctor & Gamble, and Cisco Systems. “That’s because succession planning processes are not transparent and may be less systematic than you would expect,” says Stanford Graduate School of Business faculty member David Larcker, who codirected a new study about CEO succession by the Stanford University Rock Center for Corporate Governance and The Institute of Executive Development (IED).

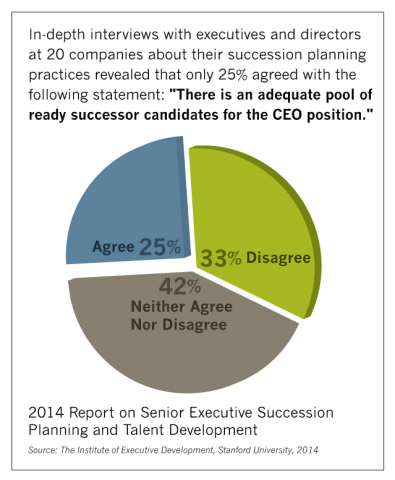

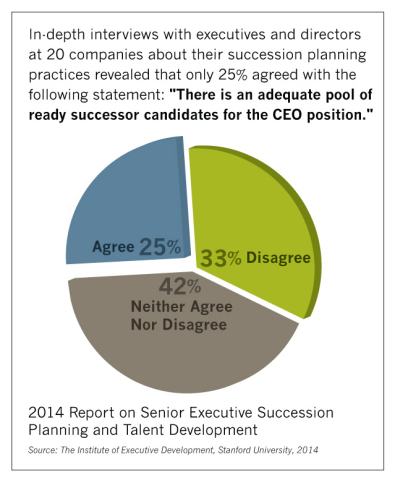

The “2014 Report on Senior Executive Succession Planning and Talent Development,” coauthored by founder and CEO of IED Scott Saslow, is based on in-depth interviews with executives and directors at 20 companies regarding their succession and executive development practices. The researchers found that only 46% of respondents have a formal process for developing successor candidates for key executive positions. What’s more, only 25% of respondents agreed that there was an adequate pool of ready successor candidates for the CEO position at their companies.

“These findings are surprising given the importance that strong leadership has on the long-term performance of organizations,” says Professor Larcker. In fact, related research shows a negative relation between the length of the succession period and the future operating results of a company.

“The corporate leaders we interviewed all believe that succession planning is vitally important, but the majority do not think that their organizations are doing enough to prepare for eventual changes in leadership, nor are they confident that they have the right practices in place to be sure of identifying the best leaders for tomorrow,” relates Larcker.

“Most company directors greatly underestimate the difficulty, time, and cost associated with CEO and C-suite succession planning,” adds Saslow. “They fail to recognize the need for a strategy for this critical business process, they haven’t had great exposure to what other organizations are doing, and they haven’t thought through what their own organization should be doing given its unique set of circumstances. This is more than lost upside opportunity; it puts many organizations at risk of having unstable executive leadership.”

Key findings of the study include:

- Companies do not know who is next in line to fill senior executive positions. According to respondents, organizations often do not make the connection between the skills and experiences required to run the company and the individual candidates who are best suited to eventually assume senior executive positions. These sentiments are in line with results from a 2010 study that showed 39% of companies do not have a single internal candidate who they deem prepared to immediately assume the CEO position, and only 54% are actively grooming someone for the role. Meanwhile, some boards believe it is simpler to choose an outsider because the company can outsource the succession process to a recruiting firm who will source candidates, conduct assessments, and facilitate a recommendation.

- Companies do not have an actionable process in place to select senior executives. According to the study, half of boards believe they have an effective succession plan in place, yet only 25% report having an adequate pool of successor candidates for the CEO role and other key C-suite positions. “The problem tends to be cultural,” observes Saslow. “The majority of companies do not have honest and open discussions about executive performance, nor do they allocate sufficient time to the process of identifying and grooming successors.”

- Companies plan for succession to “reduce risk” rather than to “find the best successors.” Respondents were most likely to view succession planning in terms of its potential to reduce future downside risk rather than producing shareholder value benefits through the identification of strong and appropriate leadership. As Larcker explains: “This is due in part to the scrutiny of regulators, rating agencies, and other market participants that emphasize the risk management and loss minimization aspects — rather than value creating elements — of succession.”

- Roles in the succession planning process are not well defined. Companies agree that succession planning involves the combined efforts of the board of directors, the senior management team, and support staff, such as the human resources department. Most, however, do not structure an evaluation process that formally assigns roles to each of these groups and requires their participation, and many respondents claim that the groups do not spend sufficient time meeting together.

- Succession plans are not connected with coaching and internal talent development programs. Succession planning and internal talent development are treated as distinct activities rather than one continuous program to gradually develop leadership skills in the organization. Tellingly, only 46% of respondents report that the board is involved in succession planning and talent reviews for key executive positions. As a result, “The board of directors does not have sufficient insight into the skills and capabilities of the senior management team and is not prepared to determine which executives are most qualified to replace an outgoing CEO or C-suite member when a succession event occurs,” says Saslow.

To improve organizational succession and talent development programs, here are just a few of Saslow’s and Larcker’s recommendations:

- Assign ownership and roles. One of the biggest reasons that organizations fail at succession is that they do not assign ownership and accountability to the process, explains Larcker. He says an independent chairman or experienced outside director should have primary responsibility — ideally someone who has considerable experience guiding CEO succession efforts. Other board members, the CEO, senior executives, and support staff should be assigned specific roles and held accountable for measurable results.

- Map the future operating and leadership skills required of each executive position and benchmark executives against these skills. Executives should be evaluated in terms of their ability to achieve the requirements of their current role and their potential to assume different or larger roles in the organization.

- Cast a wide net. Because an organization and its strategy are constantly evolving, the skills needed to run the organization in the future might not be the same as they are presently. Executive talent should be evaluated in terms of its ability to meet future — not just past or current — needs.

- Be comprehensive and continuous. Succession is not episodic. It should be treated as a continuous practice, whereby management and the board prepare for transitions at any time and at multiple levels throughout the organization.

- Get strategic assistance when necessary. Companies should survey the practices of other corporations and integrate the ones that are best suited to their current structure and situation.

For more detailed results and in-depth recommendations, the study is publicly available at http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/cldr/research/surveys/talent.html.